A Minimal Tracker Called SunVox

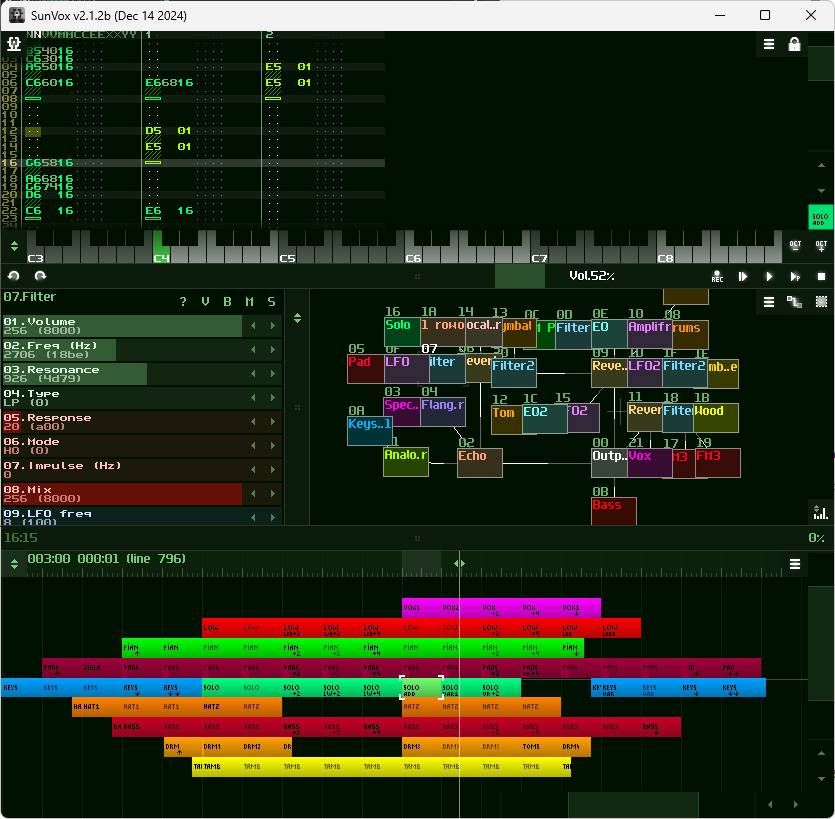

I’d like to introduce a unique music production software called SunVox. Below is a screenshot of SunVox, and at a glance, with its keyboard, timeline, folder-like sections, and lines of numbers, the UI may seem a bit strange. You might also think it's rather compact for a DAW.

This belongs to a category of music production software called a tracker. However, the term “tracker” might not ring a bell for many people, so let’s briefly look back at the history of trackers first.

History of Trackers – 1987: The Original and the Clones

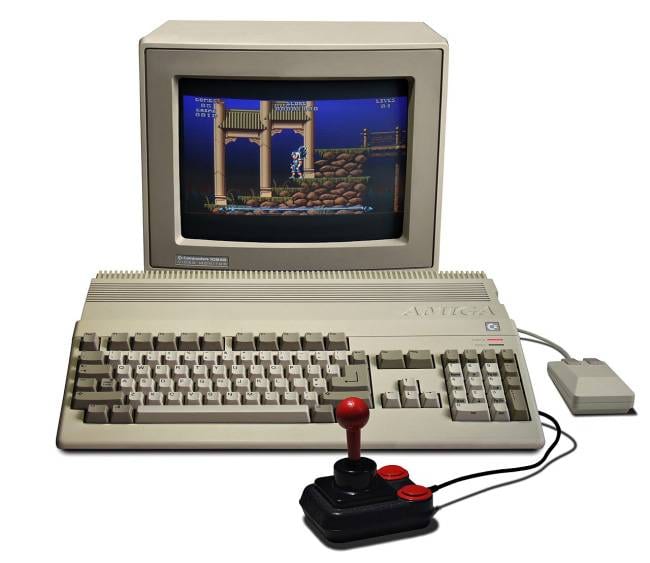

The history of trackers is actually quite long. The original tracker was “The Ultimate Soundtracker”, developed in 1987 by composer and engineer Karsten Obarski as software for creating game music on the Amiga computer by Commodore.

Amiga500, CC BY-SA 2.5 (Source: Wikipedia)

The mechanism of “The Ultimate Soundtracker” was to place very short 8-bit sampled sounds along a timeline on four pre-prepared tracks. The samples varied — some were one-shot percussion hits, others a measure-long loop, and so on. These could be played back with pitch changes, looping, and free combinations, in a simple yet effective manner. This enabled composition. The concept could be described as a toy version of the high-end workstation Fairlight C.M.I. of the time.

One notable feature was that both the sequence data and the samples were included within the song file itself. The file extension for these original files was .mod. With creative use, this system allowed for the production of fairly rich sounds with small data sizes. As a result, it was not only suitable for electronic sounds. Despite quality limitations, even acoustic-style music was possible depending on the ingenuity of the composer.

Back in 1987, music production on PCs mainly involved MIDI sequencers, where the computer controlled external sound sources. Recording audio directly onto a hard drive was still something from the future.

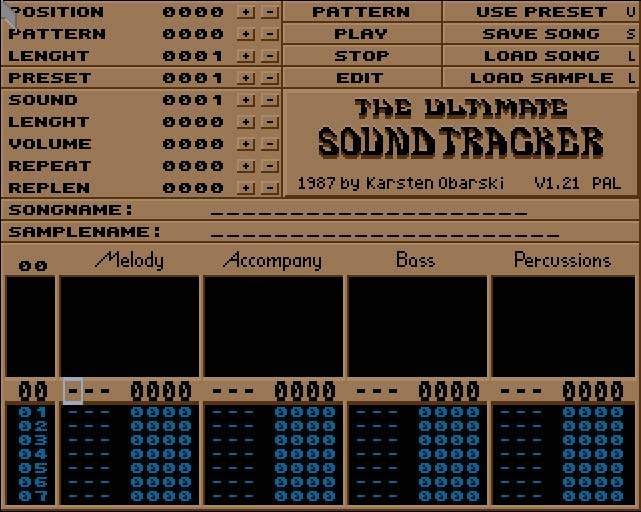

The Ultimate Soundtracker, CC BY-SA 4.0 (Source: Wikipedia)

At the time, “The Ultimate Soundtracker” was reportedly harshly criticized. For musicians who were its target users, the interface was too complex and hard to accept. As a result, the Soundtracker, which was gentle on the machine but harsh on the user, quickly disappeared from the scene.

To use an analogy, it had something in common with Reverse Polish Notation (RPN) calculators, which are now almost extinct. RPN allowed for complex calculations on low-spec calculators by letting the user handle the internal stack directly. Similarly, the logic of the tracker was simple and clear, and if users had been willing to adapt, it clearly held great potential. However, perhaps people simply were not ready for it during this era.

The tracker, which once nearly vanished, was later revived by those who were captivated by its charm. Pirate versions and clones began appearing across various platforms that were created by enthusiasts. These weren’t mere copies; features were added and improved, leading to the development of a distinct tracker culture.

Below is a sample of tracker-produced music. Back in the day, trackers were especially well-suited for creating game-like 8-bit sounds like this.

History of Trackers: The 1990s - The Dawn of the Internet Era

In the 1990s, internet networks were slow, and it was nearly impossible to send large files. Sharing music files like MP3s, which could be several megabytes in size, was considered taboo. If you wanted to let people listen to your music online, standard MIDI files were commonly used since they were just a few kilobytes. MIDI data contained only sequencing information, so the file sizes were small, but the sound source depended entirely on each user's environment, meaning it wouldn't always play back as intended.

In contrast, tracker files, which were only tens of kilobytes in size, contained their own sound sources, so there was no change in sound quality, and they could faithfully reproduce the music as intended. Reproducing distorted guitar sounds was particularly difficult with MIDI, but trackers allowed for powerful, realistic renditions that were almost like live performances. There was a strong sense of potential there. Also, being able to keep the file size small was a point of pride and skill among creators.

However, by the late 1990s, MP3s became widespread, and with the rise of RealAudio and other streaming formats, the demand for trackers rapidly declined. People were starting to listen to CD-quality music over the internet, and trackers began to lose their place.

History of Trackers: The 2000s — The Software-ization of Music Tools

The music production environment began to transform from the 1990s onward. Originally, music recording was done primarily using hardware, but with the advancement of MIDI, people started using sequencers on personal computers, and gradually software became the core of the music production setup. Eventually, DAWs (Digital Audio Workstations) combined hard disk recording with MIDI sequencers and they became widespread.

Around the early 2000s, software like Steinberg's Cubase VST gained popularity, and other companies began offering support as well. This marked the beginning of an era where even musical instruments themselves became software.

With all these changes, the need for trackers diminished significantly. Trackers, which had always been a tool for a niche group of enthusiasts, began to fade from public memory.

History of Trackers: 2025 — The Present Day

Thanks to the fact that trackers were originally a niche presence developed on a small scale, they continue to exist today as unique tools used by a small group of enthusiasts. In most cases, development is still ongoing by individuals or small teams.

Below are a few examples of trackers that are currently available.

Schism Tracker: Free and Open Source

Official Schism Tracker Website

Below is Schism Tracker, a software that retains the nostalgic MS-DOS vibe. It’s based on the Impulse Tracker. Traditional aesthetics like these are valued in the tracker community, which is why such tools continue to be accepted.

One of the defining visual features is that the tracks scroll upward during playback. This scrolling motion is part of the tracker’s identity. The sound data is written directly into this scrolling interface. You can think of it as a hybrid between a DAW’s track view and a piano roll.

Compared to early trackers, the number of tracks and channels has been significantly expanded, but the overall appearance sticks closely to traditional tracker style. As it's fundamentally operated without a mouse and with DOS-like key commands, it may feel quite foreign to users who are accustomed to modern interfaces.

OpenMPT (Open ModPlug Tracker): Free, BSD Licensed

This is the modern incarnation of the widely used ModPlug Tracker from the past. It has a somewhat old-fashioned Windows-style UI, but it’s straightforward to use with no tricky quirks—once you understand the basic concepts, you won’t get lost. You can control almost everything with the mouse, making the overall workflow easy to grasp. It also has features that cover many small but important details. It even includes a simple synth capable of 2-operator FM synthesis and more.

OpenMPT is a great tracker for beginners who want to learn the fundamentals of tracker music production. However, more hardcore tracker enthusiasts might find its more user-friendly, “mainstream” feel somewhat unsatisfactory.

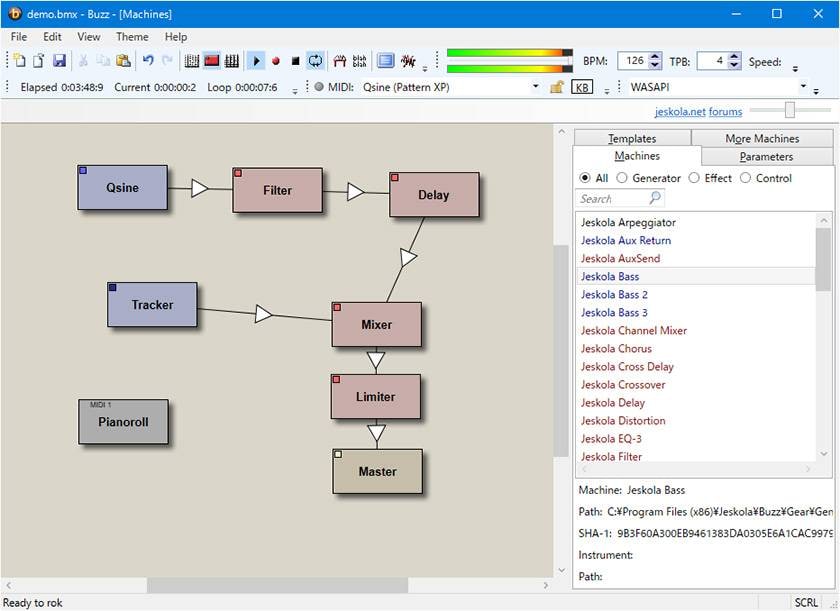

Jeskola Buzz: Freeware

Unlike traditional trackers, Jeskola Buzz takes a modern visual approach. It supports connection with external plugins like VSTs, moving in a different direction from conventional trackers.

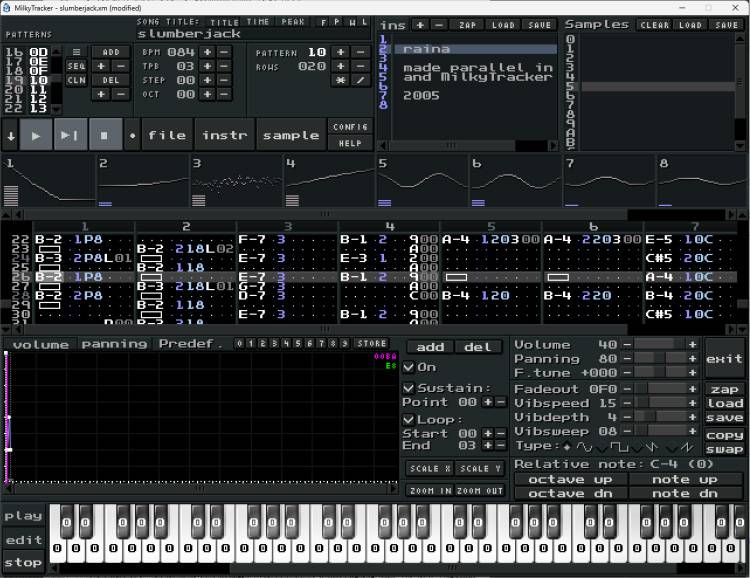

MilkyTracker: Free, Open Source

MilkyTracker’s appearance is closer to modern software, with waveform and keyboard displays. It includes a modest built-in synthesizer capable of FM synthesis and more. Still, it maintains the inherent complexity typical of trackers.

SunVox: Free (iOS and Android versions are paid)

SunVox is the main focus of this article. It continues to be developed by its creator Alexander Zolotov (Russia) since it released in 2008. While retaining the traditional tracker feel, it has evolved in a direction that avoids unnecessary expansion. Unlike Jeskola Buzz, which actively interacts with external plugins, SunVox aims to be a self-contained environment without relying on external sources.

Therefore, in addition to samples, it includes full-fledged synthesizers and effects. Although it packs many features, it avoids bloat and keeps the program size compact at around 3MB.

The dense UI is designed so that you can always see the whole picture at a glance. While maintaining that usability, it can be scaled down endlessly, even showing a sense of playfulness visually. The traditional tracker spirit is inherited only in essence, while everything else creates its own unique world.

SunVox requires no additional software and works entirely on a computer hardware setup that can be used even without a MIDI keyboard, making it appealing to minimalists. Above all, SunVox offers a gadget-like fun experience.

Anyone with even a bit of programming experience will likely be impressed by Alexander Zolotov’s remarkable programming skills. The operating environment that SunVox supports is extraordinary. It runs not only on Windows, Mac, and Linux as expected, but it also supports iOS and Android. Even more impressively, it supports Windows CE and Palm.

Almost all of the program is self-written—from fonts to the entire UI, everything is completely original, and it’s believed that even the compiler was custom-made.

Below are some samples that demonstrate the use of built-in synthesizers and effects.

Next time, I would like to consider SunVox’s position in today’s music scene.

The “sound & person” column is made up of contributions from you.

For details about contributing, click here.

![[2025 Edition] 4 Recommended FREE Apps for Guitarists to Practice Playing By Ear/Apps You Can Buy That Are Also Convenient!](/contents/uploads/thumbs/5/2025/6/20250604_5_31602_1.jpg)

厳選!人気のおすすめオーディオインターフェイス特集

厳選!人気のおすすめオーディオインターフェイス特集

DTMセール情報まとめ

DTMセール情報まとめ

スタジオモニタースピーカーを選ぶ

スタジオモニタースピーカーを選ぶ

機能で選ぶ オーディオインターフェイス

機能で選ぶ オーディオインターフェイス

DTMに必要な機材

DTMに必要な機材

DTM・DAW購入ガイド

DTM・DAW購入ガイド