Continuing from the previous article, let’s take a closer look at standard tuning.

■ Is standard tuning still ideal for the modern era?

The reason we’ve settled on standard tuning likely stems from the importance placed on open-string chords. This made sense in a time when acoustic instruments, with their relatively poor resonance, had to rely solely on their natural sound to carry the music.

However, the environment surrounding instruments has changed significantly. The introduction of electric amplification has fundamentally shifted the landscape. For instance, the guitars used in jazz are electric. If they had remained acoustic, they wouldn't have been able to compete in terms of volume and likely wouldn’t have been invited to jazz sessions at all.

Moreover, playing styles have become more complex. In jazz, and increasingly in other genres like rock, players rarely use basic open-string chords. Instead, they favor voicings with added tension that’s played all over the fretboard.

Considering this, standard tuning is most useful in genres that rely heavily on open-string chords, like singer-songwriter styles or traditional classical music. The more technical and modern the playing style becomes, the less necessary standard tuning appears to be.

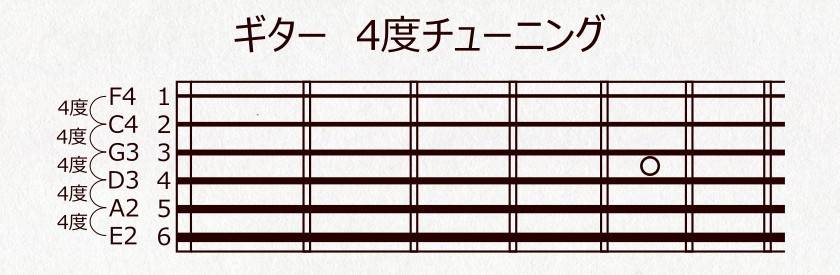

■ Fourths Tuning

Tuning in perfect fourths can be considered to be a beautifully logical tuning for the instrument. As I mentioned above, in certain genres, the need for standard tuning is becoming less relevant. However, very few players today actually tune in fourths. One notable exception might be jazz guitarist Stanley Jordan.

When playing single-note solos, tuning in fourths offers a major advantage, as all strings can be treated as melody strings. It also makes scales easier to play.

As for chord playing, if you’re not relying on open strings or full six-string chords, then there’s no issue at all. In fact, the main reason to play all six strings at once is to increase volume when playing acoustically. If you're using an amp, this is no longer necessary. Depending on the tone you’re aiming for, playing fewer notes at a time can often be better, since too many simultaneous notes can create muddiness in the sound.

Reducing the number of strings played at once brings even more advantages to fourths tuning. One major benefit is that the number of chord shapes and other forms you need to memorize decreases dramatically. In fact, the learning cost can be reduced by half or even a third. For jazz guitarists or those who play technically demanding styles, I strongly recommend seriously considering fourths tuning.

On the other hand, the main drawback of fourths tuning is that it becomes harder to play existing songs as they are. Some of what you've learned through standard tuning may no longer be applicable, and you’ll likely need to relearn certain techniques. It can also be difficult when it comes to teaching or being taught, as most materials and instructors teach standard tuning. For some, this may be a critical disadvantage.

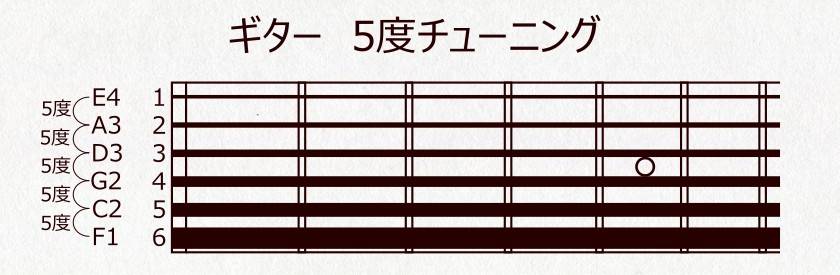

■ Fifths Tuning

While we’re on this topic, let’s briefly touch on fifths tuning. Instruments like the cello and the violin are tuned in perfect fifths. Since the scale length of a cello is quite close to that of a guitar, this kind of tuning isn’t entirely unreasonable. It’s effective when you want to cover a wide range of notes from a single position and it also lends itself well to more open-voiced chord playing.

Guitarist Allan Holdsworth, for example, experimented with guitars tuned in fifths at one point. However, since guitars have six strings, there were practical limitations, such as string gauge and tuning peg tension, that prevented him from using a perfect fifths tuning. He ended up tuning the lowest string, F, up an octave. In interviews, he mentioned that only four strings were actually doable. It’s likely he wasn’t satisfied with the overly boomy tone of the fifth string.

By the way, if you tune the 6th string in fifths without raising the octave, it ends up just a half step above a bass guitar’s lowest note (F), which brings a number of practical issues. Realistically, fifths tuning is probably only viable with five strings.

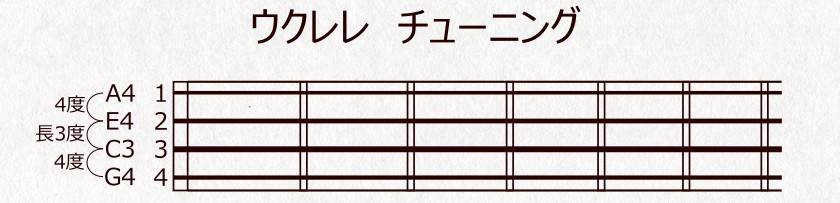

■ The Ukulele’s Mysterious Tuning

Stepping away from guitars for a moment—the ukulele’s tuning is somewhat similar to the guitar’s 1st through 4th strings. As shown below (not pictured here), in what’s called “standard tuning”, the 4th string is not the lowest pitch; it’s actually higher than the 2nd string.

Despite having only four strings, this tuning includes a major third interval that’s just like guitar tuning, which makes it quite unusual. Logically, you might assume that with only four strings, tuning in fourths or fifths would make more sense. But historically, the ukulele seems to carry influences from Renaissance guitars.

Depending on how you look at it, this tuning is similar to a six course lute tuning with the 1st and 6th courses omitted. In that framework, the 1st and 2nd strings serve as melody strings, while the 3rd and 4th strings function more as accompaniment.

Another curious aspect is that the 4th string is tuned an octave higher than expected, which may feel strange at first. However, if we consider the ukulele as primarily an accompaniment instrument, this tuning makes sense—the upstrokes and downstrokes produce a more balanced, uniform sound.

It also reflects a preference for bright, shimmering high frequencies over low-end tones. If low frequencies are needed, the assumption seems to be that you would simply play with a bass instrument in an ensemble.

Rather than focusing on specs like range or tuning logic, the ukulele conveys a more relaxed and open-minded musical philosophy, which is one that values emotion and atmosphere over technical perfection.

■ Finally

In my opinion, standard tuning is not ideal—it’s more of a compromise because it sacrifices many possibilities in order to allow full six-string basic chords using open strings. In today’s world, with the development of electronics, it’s no longer such an outstanding tuning. Still, as the de facto standard with an enormous legacy behind it, it remains a safe and practical choice.

On the other hand, fourths tuning has finally entered an era where it can begin to shine. (Though it’s been over half a century since the groundwork was laid…) Transitioning from standard tuning only requires raising the 1st and 2nd strings by a semitone, so there’s no need to even change your strings—making it an easy switch.

For players who pursue originality and technical expression, I highly recommend giving it a try.

What does puzzle me, though, is that Allan Holdsworth, whom I personally consider the most evolved guitarist, experimented with fifths tuning but, as far as I know, he never played in fourths tuning. The fact that he didn’t try it might suggest there's some major blind spot I’m not seeing.

However, I personally haven’t found any downsides for now.

The “sound & person” column is made up of contributions from you.

For details about contributing, click here.

7弦ギタースタートガイド

7弦ギタースタートガイド

DIY ギターメンテナンス

DIY ギターメンテナンス

弦の張り替え(アコースティックギター)

弦の張り替え(アコースティックギター)

弦の張り替え(エレキギター)

弦の張り替え(エレキギター)

音を合わせる(チューニングの方法)

音を合わせる(チューニングの方法)

ギタースタートガイド

ギタースタートガイド