■ Guitar Tuning

This time, I would like to explore the mystery of standard guitar tuning from both a historical and structural perspective.

Guitar strings are generally tuned in perfect fourths, except for the interval between the 3rd and 2nd strings, which is a major third. Many players feel a sense of inconsistency here. There are various theories about the origin of this tuning, but most explanations are vague or glossed over. Some even link it to chord progressions, which I find a bit questionable.

Personally, I lean toward the commonly cited reason that the tuning was designed with chord shapes in mind, but I’ve tried to dig deeper and explain it in a more convincing way. I aimed to keep it simple, but the explanation ended up being long, so I’ll break it down into two parts.

■ Basic Tuning is Usually in Perfect Fifths and Fourths Tuning

Violins and cellos are tuned in perfect fifths. This is because they are primarily used for playing single-note lines and have only four strings, so tuning in fifths allows for a wider range either in a single position or across the entire instrument. Musically, the perfect fifth is also the next most harmonious interval after the octave, which makes it a logical choice. In earlier times, when electronic tuners weren’t available, tuning by ear was essential, and fifths offered a more intuitive and stable reference.

Now, let’s look at the contrabass, the lower member of the violin family. Unlike its higher-pitched relatives, the contrabass is tuned in perfect fourths. This is partly due to the longer string length, which makes fifths physically harder to play, and also, it doesn’t require as wide a range as a bass instrument. Interestingly, the double bass was not originally part of the violin family but rather a kind of auxiliary instrument, so its tuning likely stems from a different conceptual origin.

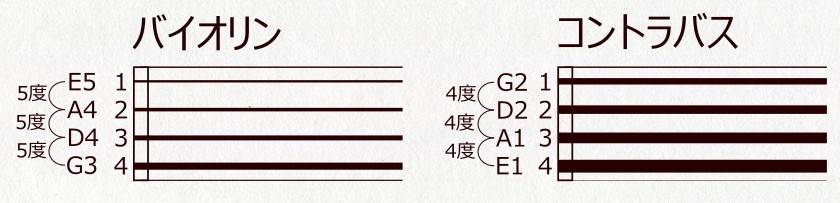

Let’s compare the tunings of the violin and contrabass.

As shown in the diagram, the order of the strings is essentially reversed between instruments tuned in fifths and those tuned in fourths. Since a perfect fifth up is the same as a perfect fourth down, the two tunings are actually quite similar. In practice, this means that playing patterns are simply mirrored, so there’s little confusion when switching between them.

Historically speaking, it’s fair to say that Western string instruments are primarily based on either perfect fifth tuning or its inverse, perfect fourth tuning.

■ What If the Guitar Were Tuned in Fourths?

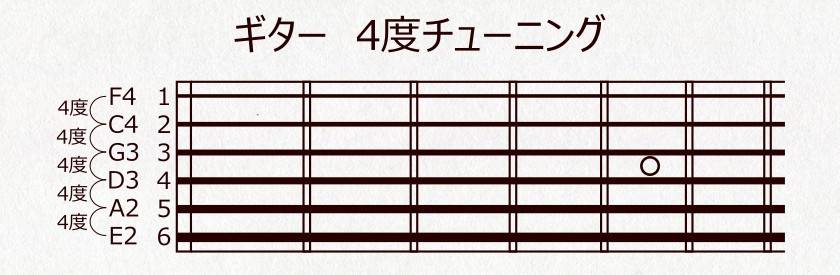

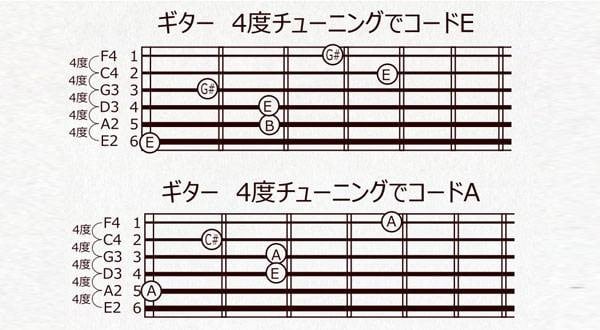

Based on the logic discussed above, one might assume that tuning a guitar in perfect fourths would make sense. It has a relatively long scale length and is often used for playing chords. In a fourths tuning, the string intervals would look like this:

This setup essentially raises the 1st and 2nd strings of the standard tuning by a half step, resulting in all strings being tuned a perfect fourth apart.

So, what's the downside? After all, extended-range electric basses such as 6-string models often use all-fourths tuning. The key difference is that bass playing is primarily single-note based, not chordal. I’ll dive deeper into the implications and considerations of fourths tuning in the next article.

■ What If the Guitar Were Tuned in Fifths?

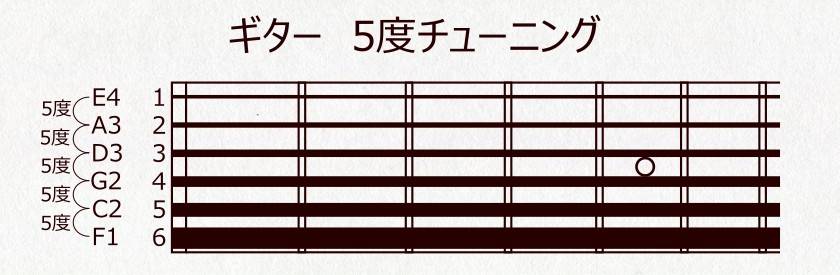

Since the guitar has a scale length similar to that of a cello, it might seem that tuning it in fifths wouldn’t pose a major issue. However, one key difference lies in the way the instruments are held. On a guitar, it's more difficult to stretch your fingers wide across the frets, making scale playing more challenging. That said, the presence of frets might offset this drawback somewhat.

The main reason guitars aren’t tuned in fifths likely comes down to chords: tuning in fifths offers little advantage for harmonic playing. The resulting voicings would be too open, making chord playing impractical. Additionally, tuning six strings in fifths would yield an extremely wide range. Extending downward would encroach on bass guitar territory, and achieving good resonance on such low notes with an acoustic instrument would require a much larger body. Conversely, extending upward would require very thin, and very breakable strings.

In short, it seems that a 5-string or 4-string instrument is more suitable for fifths tuning.

■ Lute Tuning

Now let’s take a look at the lute, which is often considered to be an ancestor of the modern guitar. While there are several candidates for the guitar’s lineage, we’ll focus on the lute for now. Lutes came in various forms; the 6-course, 8-course, and even the 13-course instruments. A course refers to a set of strings played together, typically consisting of one or two strings per course. Since early instruments lacked the volume and brilliance of modern ones, pairing strings was a way to enrich and amplify the sound.

Lute tuning is quite similar to modern guitar tuning. To replicate it on a guitar, you can lower the 3rd string by a half step and place a capo on the 3rd fret, and voilà! Renaissance vibes achieved. Typically, the higher strings (treble courses) handled the melody, while the lower ones (bass courses) were used for accompaniment, giving the instrument a visually and functionally split role.

The way to play it is similar to that of a classical guitar, allowing the performer to manage both the melody and accompaniment simultaneously. However, lute necks generally only had about eight frets (plus a little more), which meant open strings were heavily relied upon. The existence of multi-course lutes further emphasizes this point.

From this, we can infer that fourths tuning was the ideal. The presence of a major third between the 3rd and 2nd strings seems to have been a compromise. So, why did this compromise occur? Let’s explore that next.

■ Why the Major Third Interval Became Necessary

In the case of the lute, it’s a musical instrument that frequently uses open strings to produce chords. What’s also important is the instrument’s lowest playable note, which players often want to emphasize. Guitarists and bassists tend to prefer keys like E and A, largely because these correspond to the lowest notes available as open strings.

The sound of open strings differs from fretted notes in that it sounds brighter and more resonant, often louder, making the performance easier. This is especially true for classical acoustic instruments, which tend to have weaker natural resonance, so relying on open strings is the natural approach.

Therefore, on the lute, tuning was developed around chords based on the open low notes G and C, leading to the “G C F A D G” tuning. This is similar to how guitarists prioritize chords based on E and A. The key point here is that these chords are basic triads without extra tension notes.

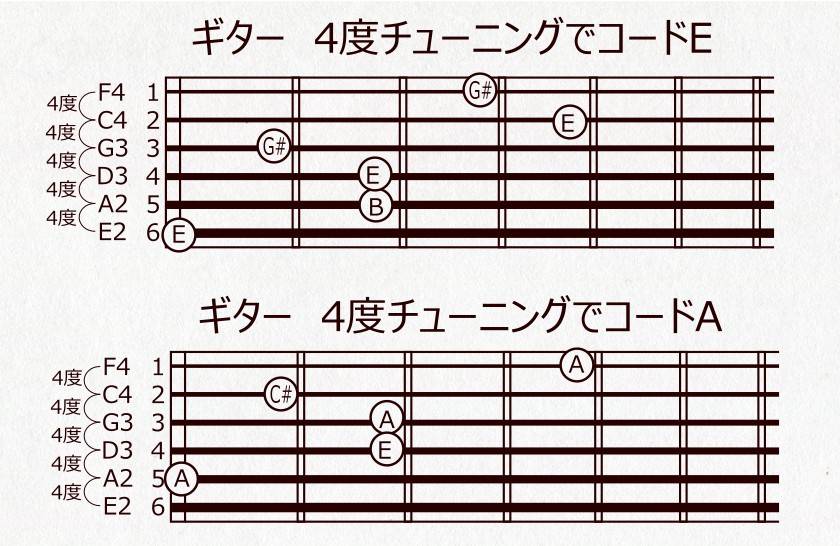

What happens if you tune a guitar entirely in fourths and try to play E and A based chords? That’s what we’ll consider next.

For an E chord with the 6th string as the root, the open 2nd string (C) and open 1st string (F) create dissonance, making it difficult to finger the chord properly. You can only use the open string as the root note. For an A chord with the 5th string as the root, the 2nd string is not a problem, but the open 1st string (F) becomes troublesome. Again, only the root note can be played as an open string. The same applies when barring chords since the sound of the 1st and 2nd strings becomes problematic depending on whether the root is on the 6th or 5th string.

This is why the all-fourths tuning is abandoned and the 1st and 2nd strings are tuned down by a half step. In the case of the lute, the 3rd string is also tuned down a half step to join the 1st and 2nd strings, making a nicely balanced set. It seems that the melody strings are kept in fourths tuning because the melody playing is emphasized. When considering these three strings as melody strings, it seems the lute focused on the melody.

This way, open chords can be played without difficulty, and melodies become easier to play.

The difference between the guitar’s and lute’s tuning lies in the half-step difference on the 3rd string, which seems to be largely influenced by the lowest note. If a guitar with the lowest note E were tuned like a lute, the 3rd string would become Gb, which corresponds to a black key on a piano keyboard. This may have been avoided by raising that note a half step. Alternatively, it might have been the result of prioritizing the instrument’s role as an accompaniment instrument rather than a complete solo instrument.

If you think about it, if the guitar’s lowest note had been tuned one whole step lower than the current E, to D, the tuning would be DGCEAD, which is the same as the lute’s tuning.

For these reasons, the regular tuning spread widely. It prioritizes volume and tone quality, uses open strings frequently, and allows basic chords to be played across many strings. However, this mainly applies to classical acoustic instruments with poor resonance. Today, instruments, strings, playing styles have evolved greatly, and electronics have become a major factor. Even in such instances, can regular tuning still be considered a convenient tuning?

The column "sound&person" is made possible by submissions from everyone.

For more details about submissions, click here.

7弦ギタースタートガイド

7弦ギタースタートガイド

DIY ギターメンテナンス

DIY ギターメンテナンス

弦の張り替え(アコースティックギター)

弦の張り替え(アコースティックギター)

弦の張り替え(エレキギター)

弦の張り替え(エレキギター)

音を合わせる(チューニングの方法)

音を合わせる(チューニングの方法)

ギタースタートガイド

ギタースタートガイド