Are you familiar with the late Ryuichiro Senoo? He was a pioneering figure in Japanese blues harp, and someone I consider to be my mentor.

Well, I say “mentor”, but in truth, I never actually met him. I simply read his blues harp lessons serialized in this music magazine long ago, and I took it upon myself to regard him as such. If he’s up in heaven, he might be falling over laughing at this, and his real disciples might be quite upset. So let me apologize in advance—I’m terribly sorry.

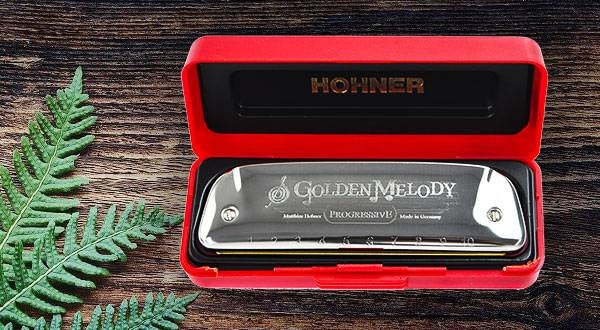

A few years ago, the news of Mr. Senoo’s passing prompted me to pick up the harmonica again after a hiatus of several decades. Since then, I’ve been completely hooked not only on the blues harp, but also on the chromatic harmonica. My collection just keeps growing. Well, no matter how many I own, they don’t take up much space like other instruments, so I guess it’s fine.

Back in my teens when I first started playing blues harp, I was under the impression that I could perfectly play the Sesame Street theme song. Only now do I realize that the version I aspired to was a performance by the great Toots Thielemans. I’m constantly amazed at how clueless, lacking in musical sensibility, and tone-deaf I was back then. It really drives home how humans can't properly judge things that are beyond their own level of perception.

And so, with a wish to share the laid-back charm of the harmonica with the world—especially in these trying times—I decided to put together this little piece. By the way, if I were to give it a playful title in kanji, it would be “吸ったもんだハーモニ閑話” (Suttamonda Harmonica Kanwa). Yes, with pun intended. Sorry about that.

Now then, as you may know, "Blues Harp" is actually a registered trademark of the Hohner company. As a general term, it’s often referred to as a “10-hole harmonica” due to the number of holes, or as a “diatonic harmonica” to distinguish it from a chromatic one. It’s also sometimes called a “Richter harmonica” after Joseph Richter, who devised its note layout. In this article, however, I’ll be using the more widely recognized and familiar term “blues harp”.

(Note: “Chromatic” refers to the chromatic scale, including semitones. “Diatonic” refers to the whole-tone scale—like the white keys on a piano.)

What’s truly remarkable about the blues harp is that, despite being only about 10 cm long and having just 10 holes, it can produce a range of three octaves. Since each hole can produce two different notes—one when you blow and another when you draw—you get 20 notes in total across the 10 holes...

Huh? To cover three octaves, you’d need 7 + 7 + 7 + 1 = 22 notes, right? So then, to fit it into 20 notes, you’d have to omit 3 notes...

Wait a second—22 minus 3 equals 19 notes, doesn’t it? What’s going on here?

Sorry for throwing in some unexpectedly advanced math out of the blue. But here’s the thing: the low G note can be played both when blowing and drawing, so you end up with 19 notes + (draw/blow G) = 20 notes. That’s how it works.

(Figure 1)

Normally, C–E–G (do–mi–so) are blow notes, and D–F–A–B (re–fa–la–ti) are draw notes. But since the low G (so) can be played both by blowing and drawing, it allows for chords like G–B–D–F to be played. In other words, by taking a big bite of the harmonica and alternating between blowing and drawing, you can produce tonic and dominant 7th chords in succession. Joseph Richter, the man who came up with this — is an absolute genius!

Now, some of you may be wondering, “So what about the three missing notes — are they just gone for good?” Fear not. Thanks to the famous technique known as “bending,” those notes can indeed be played.

Bending is a technique where you blow or draw forcefully, or draw bend or blow bend, to significantly change the air pressure inside the chamber, which pulls the pitch downward. However, there's a catch: you can only bend the higher of the two notes in a hole downward toward the lower one. Still, that's more than enough to make up for the missing three notes.

The low F can be bent down from the 2nd hole G, the A from the 3rd hole B, and the high B from the 10th hole C. And with that, the full diatonic scale across all three octaves becomes playable. Once again, Richter proves to be a genius!

(Figure 2)

Surely, there isn’t a blues harp player who can’t do bends, right? Right?

Just in case, here are some tips. First, focus on just one hole—around the 3rd hole is good. Concentrate on that hole and inhale sharply. It’s like slurping a single noodle from a bowl of cold soba, or sipping a frozen smoothie through a straw. Once you get the hang of it, the pitch should drop easily.

If you still can’t get it right, maybe your mouth cavity is too small when you play normally. Try creating a space inside your mouth about the size of a quail egg while playing. Not only will bending become easier, but your tone will improve too. Give it a try!

What’s that? You want to play even more non-diatonic notes? Wait, you can’t do blues without flat 3rd, flat 5th, and flat 7th? How can it be called a blues harp if you can’t play the blues?!

You’re absolutely right. For those of you making such demands, I present this secret weapon: 2nd position.

Since the blues harp is diatonic, the basic rule is to use a harmonica in the same key as the song. However, the 2nd position technique involves using a harmonica in a key that’s a perfect fourth above the song’s key. For example, if the song is in C, you play on an F harmonica; if the song is in A, you use a D harmonica.

What happens then? The song’s scale—C D E F G A B C—becomes G A B C D E F G on the harmonica. And voilà! The flat 7th (B♭ in the key of C) naturally comes out, and the flat 3rd and flat 5th (your blue notes) can be played using bends. This is where the blues harp really shines! In blues and rock music, this 2nd position playing is actually the first choice.

(Figure 3)

Well, I’ve rambled on about some very basic aspects of the blues harp, but actually, there’s an even trickier technique than bending called overblowing (or overdrawing). By doing this, you can play all the chromatic notes, though if you want to do that, it’s probably easier just to use a chromatic harmonica.

What really makes the blues harp special, though, is the ability to grab it firmly and play rhythmic “bumps” — that punchy blow-draw groove. Leave the flashy melodies to other instruments, and let those sweet blues harp rhythmic bursts loose!

The “sound & person” column is made up of contributions from you.

For details about contributing, click here.

TOMBO ハーモニカ特集

TOMBO ハーモニカ特集

ハーモニカスタートガイド

ハーモニカスタートガイド

HOHNER ハーモニカ特集

HOHNER ハーモニカ特集

SUZUKI ハーモニカ特集

SUZUKI ハーモニカ特集

超オススメのフレーズ道場 アコースティックギター

超オススメのフレーズ道場 アコースティックギター

ギター名人ラボ

ギター名人ラボ