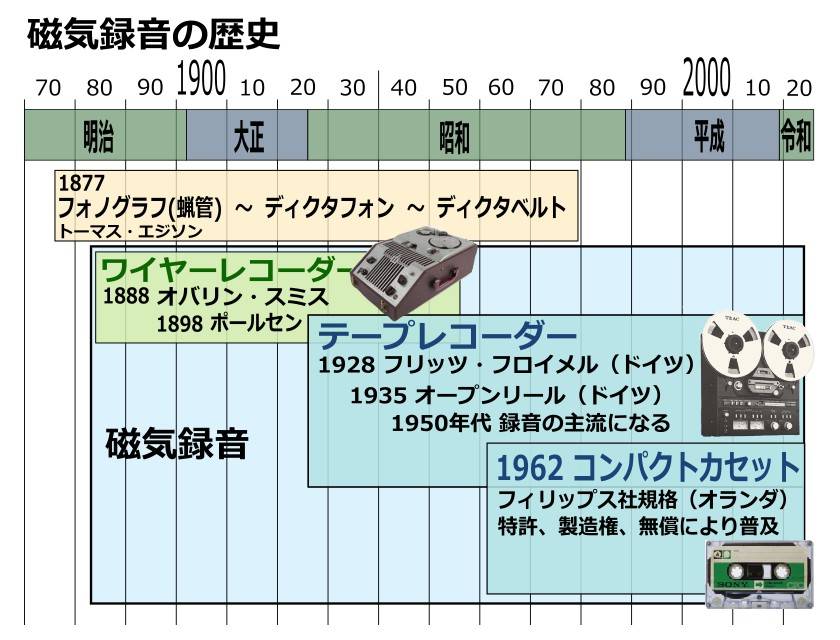

When we think of tape recorders, many people may envision compact cassette tapes, but here, I would like to explore the history of the large tape recorders known as open-reel tape recorders.

■ 1928 - Tape Recorder - Fritz Froelich (Germany)

The tape recorder is said to have been invented in 1928 by German engineer Fritz Froelich. At that time, wire recorders were difficult to use but they were being used worldwide. If the wire became tangled or broke, it had to be welded. Froelich overcame the drawbacks of the wire recorder and invented a tape recorder with media that was lighter and easier to make. He laid the foundation for the current magnetic tape technology by adhering magnetic powder onto film or paper. During this period, vacuum tube technology had already become available, and the technology for amplification devices was there, so the groundwork for developing magnetic recording devices was already in place. However, the quality of the tape was poor and the sound quality was not very good.

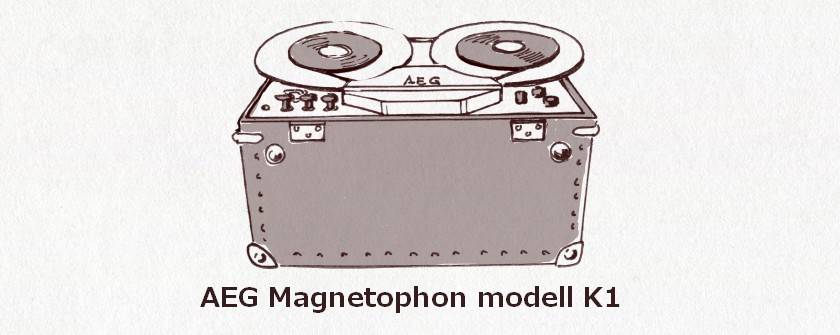

■ 1931–1935 - AEG, BASF (Germany) - Magnetophone K1

The German company AEG bought Froelich’s patent and began actively advancing the development of magnetic recording. The basic technology necessary for tape recorders was established by AEG.

The development of the tape itself was handled by the chemical manufacturer I.G. Farben (later BASF) in Germany, which completed the practical magnetic tape. It was a combination of cellulose acetate base and iron oxide.

In 1935, AEG introduced the Magnetophone K1. Within a few years, it was adopted by nearly all the broadcasting stations in Germany.

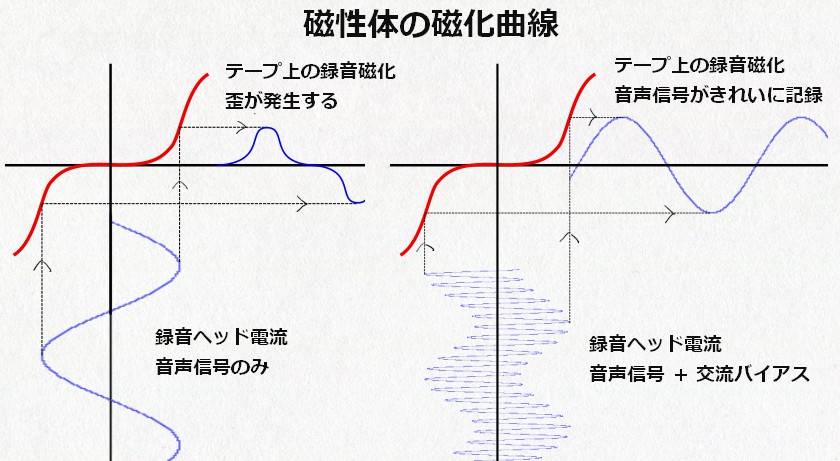

■ 1942 - The Key to High Sound Quality: AC Bias

The adoption of AC bias dramatically improved sound quality. Due to the wartime period, this information did not leave Germany. While tape recorders were used in radio broadcasting, other countries claimed that the sound seemed like live broadcasting. This suggests that the sound quality was overwhelmingly high.

The AC bias, which was essential for improving the sound quality of magnetic recording, was invented in multiple places around the world without any information sharing. The concept of AC bias itself had been studied since the 1920s, but not specifically for magnetic recording. In the 1930s, the United States adopted AC bias for wire recorders, improving their sound quality. In Germany, the improvement of sound quality using AC bias started in 1940, seemingly by accident. In Japan, in the 1930s, Kenzo Nagai of Tohoku University conducted experiments with AC bias for wire recorders and obtained a patent.

■ The Mechanism of AC Bias

When trying to magnetize the magnetic tape using an audio signal, it is not possible to faithfully record the sound because the hysteresis curve is not linear. This means that the magnetic tape cannot be magnetized unless the magnetic force exceeds a certain level. By mixing an alternating current (AC) signal with the audio signal, the magnetic tape can always be brought to a level where it can be magnetized, allowing for a clean recording of the audio signal. The frequency of the AC bias is set between 50kHz and 100kHz to avoid interference with the high frequencies of the audio signal.

■ The Entrance of Japanese Manufacturers

After the war, Germany's tape recorder technology became known worldwide, and since it offered higher sound quality than wire recorders, research and development of tape recorders began globally.

In the 1950s, Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (Sony), despite having very little information, entered the tape recorder market and even developed their own tapes. They also acquired the patent for the AC bias from Kenzo Nagai and used it in collaboration with NEC (Nippon Electric Company), successfully developing practical products ahead of other companies.

In the 1980s, portable tape recorders were sometimes referred to as "Densuke". "Densuke" was the title of a comic strip by Takashi Yokoyama, which had been serialized in newspapers since 1949, and it was the name of the protagonist. Due to the fact that Sony's tape recorders were often carried around for street interviews, portable tape recorders came to be called "Densuke." Sony later trademarked this name.

■ Open-Reel Standards

Since various countries and manufacturers were developing tape recorders independently, which hindered market expansion, a standardization was necessary. Open-reel tape recorders came to comply with the American NAB (National Association of Broadcasters) standard. Sony initially manufactured their tapes in 6mm width and then changed it to 6.35mm after learning that the standard width was 1/4 inch.

Tape width

| Tape width (inch) | Tape width (mm) | |

| 1/4 | 6.35 | Standard Size Sold |

| 1/2 | 12.7 | For Multi-track Use |

| 1 | 25.4 | For Multi-track Use |

| 2 | 50.8 | For Multi-track Use |

Magnetic Tape Transport Speeds

| Speed by inches/ second | Speedy by cm/ second | |

| 3.75 | 9.525 | |

| 7.5 | 19.05 | Slow speed |

| 15 | 38.1 | Normal speed |

| 30 | 76.2 | High speed |

No. of Tracks (in the case of 1/4 inch)

| Track number (1/4 inch) | |

| 2 | Stereo one-way or monaural play-back |

| 4 | 4 channels in one direction or stereo back and forth |

The wave of stereoization came in the 1950s, and tape recorders, because of their characteristics, were among the first to achieve stereo.

■ Sound Quality

When compared to the well-known compact cassette tapes, the difference in sound quality is overwhelming. This is due to the differences in tape width and the speed at which the tape is fed, resulting in a larger recording area and a greater amount of information. Additionally, the dynamic range is expanded, which also makes it more advantageous in terms of noise. In open-reel tape recorders, even without the noise reduction, the noise is not very noticeable. Open-reel tape recorders can be considered the pinnacle of analog magnetic recording.

■ Afterward

Open-reel tape recorders were expensive, large, and required careful handling, making them not easy to use. They were mostly used in professional fields that prioritized sound quality. However, with the advent of compact cassette tapes in the 1960s, they became affordable, small, and easy to use, leading to their widespread adoption by the general public. Eventually, when people referred to "tapes," they meant cassette tapes.

Professional analog magnetic recording was gradually replaced by digital recording starting in the late 1980s. The manufacturing of open-reel decks in Japan ended around 1990. By the 2000s, open-reel tape recorders were treated as antiques, and I often saw people maintaining and repairing them. Obtaining tapes has become difficult, and they are no longer produced in large quantities. However, the appeal of open-reel recorders has not faded with the digital age; instead, open-reel tape recorders are being rediscovered. In today’s world of music production, which is done on PCs, analog tape emulators are used virtually to recreate that analog feel. The compression effect known as "tape compression" still has its unique charm.

In the next issue, I plan to write about compact cassette tapes, which rapidly spread worldwide in the 1960s and are still sold as practical items today.

The “sound & person” column is made up of contributions from you.

For details about contributing, click here.

![[2024] 15 Recommended Equipment for Online Broadcasting! Get Started with Live Streaming/Gaming/Podcasting!](/contents/uploads/thumbs/2/2021/12/20211214_2_15561_1.jpg)

![[2023 Latest Edition] Overview of Some New Audio Interfaces!](/contents/uploads/thumbs/2/2021/1/20210108_2_12044_1.jpg)

Saramonic 特集

Saramonic 特集

BOYA特集

BOYA特集

ZOOM フィールドレコーダー比較表

ZOOM フィールドレコーダー比較表

TASCAMフィールドレコーダー 比較表

TASCAMフィールドレコーダー 比較表

ZOOMレコーダー 比較表

ZOOMレコーダー 比較表

TASCAMレコーダー 比較表

TASCAMレコーダー 比較表