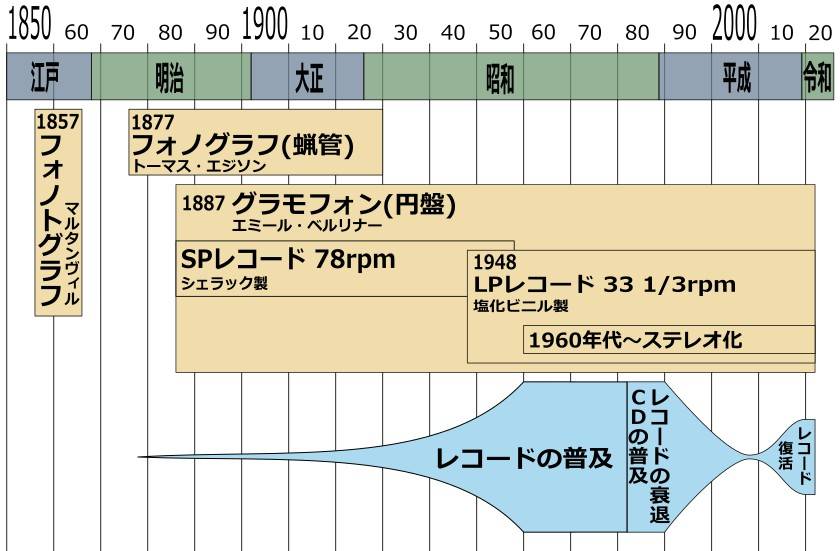

The Evolution of Record Technology with the Adoption of Electricity

■ Adoption of Electricity

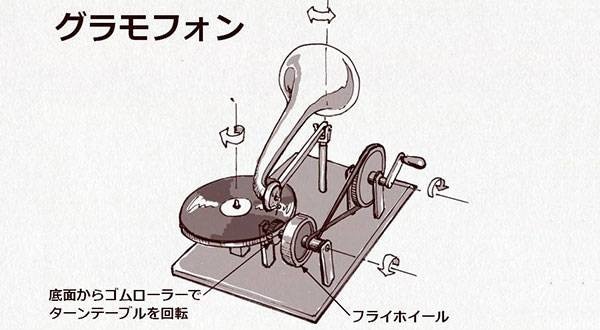

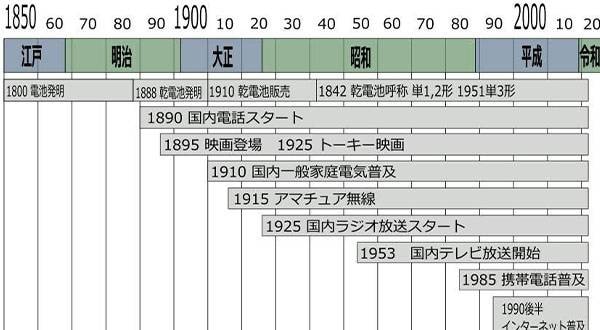

Early phonographs were completely mechanical and did not use electricity at all. Edison did use a battery-powered electric motor, but due to cost and practicality concerns, spring-driven mechanisms became the mainstream. In the 1930s, with the advent of vacuum tube amplifiers, electricity began to be actively utilized in record players. In Japan, the term denchiku (electric phonograph) came into use. The use of electricity became essential both for amplifying the sound and for powering the rotational mechanism that spins the record.

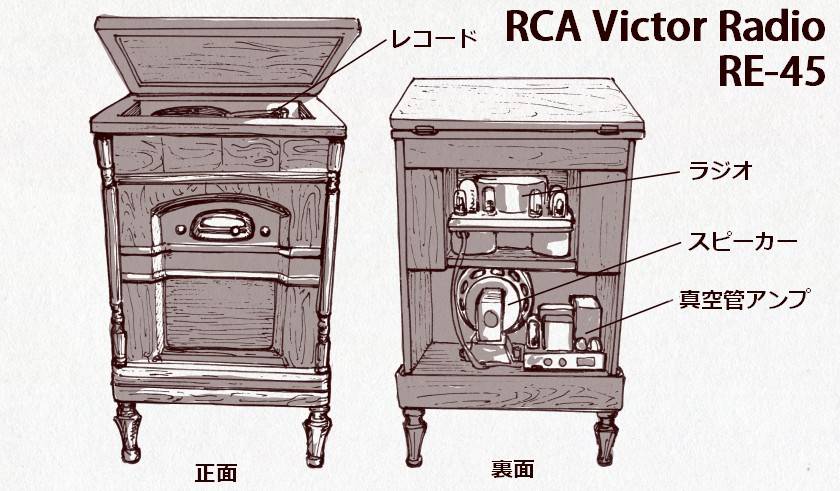

Released in 1929, the RCA Victor Radio RE-45 became a global hit. Its design resembled antique furniture, with audio equipment fully integrated into the structure. In terms of its construction, it was similar to modern separate audio systems.

■ After the SP Disc

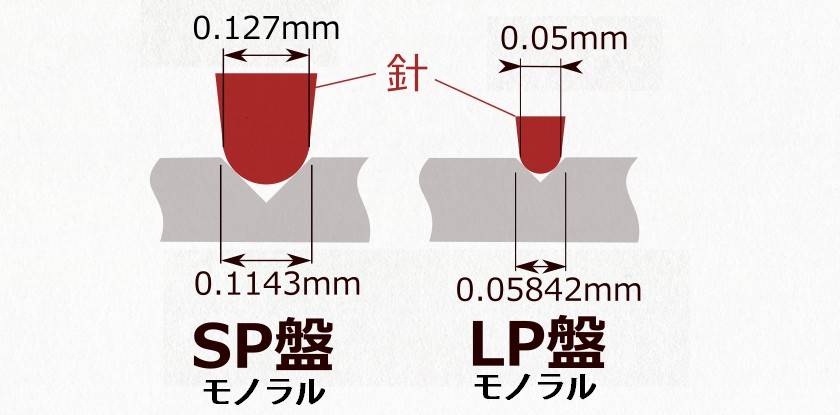

The LP (Long Play) record was first introduced in 1948 and is the current standard for vinyl records. It has a diameter of 30 cm, the same size as the SP disc. By reducing the rotation speed to 33 1/3 rpm, the LP allows for up to 20 minutes of playback per side, making it capable of much longer durations than the SP disc. The use of vinyl chloride (PVC) plastic improved the sound quality because it compensated for the drawback of slower rotation speed while also increasing durability. Additionally, by making the grooves on the record shallower and finer, it became possible to record for even longer periods. This also resulted in a smaller size for the stylus (needle).

The diagram below uses millimeters as the unit of measurement, but records were designed based on the US measurement system in inches. On records, the unit "mil" is used, where 1 mil = 1/1000 inch = 0.0254 mm.

The single (single-sided) record has the same 17 cm diameter as the EP (Extended Play) record but spins at 45 rpm. It was introduced as a replacement for the SP disc and features a large center hole that was designed with jukeboxes in mind.

EP records (Extended Play) have a 17 cm diameter and come in two types: one that spins at 33 1/3 rpm and another that spins at 45 rpm. The center hole is the same size as that of an LP. Since the EP allows for longer recording times than a single, it is called "Extended Play."

■ Material of the Phono Needle

The early phono needles were made of iron, but due to wear issues, various materials were experimented with. After the 1950s, when records became widely popular, synthetic diamonds became the standard material for the needle. However, wear could not be completely avoided.

■ 1958: Stereophonic Sound

In 1958, the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) adopted the "45-45 system" for the stereoization of records. Records started later than tapes or radio in adopting stereo sound. Around 1960, records gradually transitioned from single-channel mono to two-channel stereo. A stereo system requires two amplifiers and two speakers, but perhaps more importantly, it offers better spatial expression. Today, stereo is the standard for music. Unlike movies, more than two channels are not widely sought after in music. While there is a significant difference between mono and stereo, having more than two channels often doesn't provide substantial improvement, depending on usage. In order to save money, fewer channels are generally preferred, and two channels seem to be a convenient and reasonable choice. The effects of stereo sound were understood before the 1900s, but on records, it took about 50 years until the "45-45 system" was adopted. This method, which extracts two-channel signals from a single groove and a single needle, is a magical technology, and I would like to explain it in more detail next time.

■ 1982: The Decline and Revival of Vinyl Records

After the birth of the CD in 1982, it gradually replaced vinyl records over a period of about 10 years. The CD, being smaller and free from the noise caused by dust and scratches, was more practical and easier to handle, making the switch inevitable. Vinyl enthusiasts were dissatisfied with the sound of CDs, but for the general public who listened to music with affordable equipment, CDs probably sounded much better. The vinyl record declined in the 1990s and was no longer produced as much.

It seemed that vinyl records were doomed to disappear, but starting in 2010, vinyl began to gain attention again. Interestingly, it seems that the younger generation, who had no prior experience with vinyl, played a big role in this resurgence, which is a curious phenomenon. This surge in popularity doesn’t appear to be a fleeting trend. Ten years later, it is not unusual for new releases to be issued on vinyl. Domestic production of records has resumed, and in the U.S., vinyl sales have even surpassed CD sales.

This resurgence in vinyl can be seen as a reaction with the widespread adoption of digital music streaming and the digitalization of everything. However, instead of turning to CDs, it seems that people are drawn to vinyl because of its physical presence. Unlike CDs, which store digital data, vinyl records store analog waveforms that can be visually seen, which could be compared to the difference between digital and film photography. It’s possible that the sense of reality in digital music felt lacking, prompting people to seek something tangible. Additionally, the visual aspect of vinyl records—such as the larger 30 cm album covers—cannot be experienced with CDs. The value of visual art is evident. During the vinyl era, creating album covers was clearly a big focus.

Below is a photo of an LP cover, and the impact of this size is unparalleled. Personally, one of the most disappointing aspects of the CD era for me was the smaller size and lack of texture in the album covers. Occasionally, there are paper jackets for CDs, but still, the smaller size of a CD never feels quite as satisfying.

The “sound & person” column is made up of contributions from you.

For details about contributing, click here.

![Enchanting Instruments 22 - Voice 5 [Resonance]](/contents/uploads/thumbs/5/2021/11/20211124_5_15249_1.jpg)

PC向けDJソフトの選び方

PC向けDJソフトの選び方

ODYSSEY DJケース購入ガイド

ODYSSEY DJケース購入ガイド

Allen&Heath DJミキサー比較表

Allen&Heath DJミキサー比較表

DJケースセレクター

DJケースセレクター

PIONEER DJ 比較表

PIONEER DJ 比較表

DJを始めるのに必要なもの?

DJを始めるのに必要なもの?