- Sound House online course

- Keyborad and piano lessons for beginners

- How to read the score

How to read the score

Here are the minimum elements needed to read the score.

The music score is marked by notes and symbols according to defined rules. If you want to play the piano but you can't read the score, or you can play the instrument but not the score, it's not that difficult if you do not have the basics down. If you can read the score, it will be fun not only to play but also to listen to the music.

1. A view of the staff

The basic of score is "Stave score". Various notes and symbols are written here, and the score is completed.

Scores such as vocals, guitars, and the right-hand part of the keyboard are represented by a “t-sign”. In addition, the score of the left hand and the bass of the keyboard uses "f-symbol". Note that the treble clef and the bass clef differ in the way they represent the pitch.

By the way, the treble clef starts writing from the position of the treble (so) and the clef starts from the position of the fa (fa).

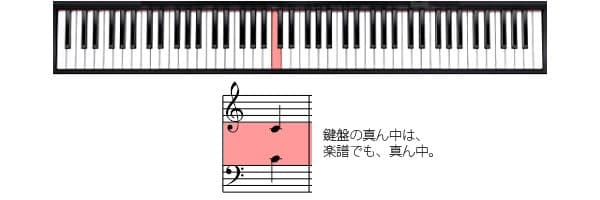

The beginning of the following treble clef is do and, at the beginning of the Bass clef is also do is the same height ( "Figure 1 do position of").

図1

2. Note length

The notes also represent the length of the note. Considering the basic note as a whole note

the half note ( ) is the half of the whole note . The half of the half note is quarter note (

) is the half of the whole note . The half of the half note is quarter note ( ), the half of is the quarter note is 8th note (

), the half of is the quarter note is 8th note ( ), the half of the 8th note is 16th note (

), the half of the 8th note is 16th note ( ), and the half of the 16th note is 32nd note (

), and the half of the 16th note is 32nd note ( ).

).

There may be a dot next to the note, which is called a dotted note.

Dotted notes play 1.5 times the length of the original note.

In addition, the rest has the same lengths, and is followed by a full rest, a 2nd rest, a 4th rest, an 8th rest, a 16th rest and a 32nd rest.

| note | When a quarter note is one beat | rest |

|---|---|---|

Whole note |

|

Whole rest |

Half note |

|

Half note |

Quarter note |

|

Quarter rest |

8th note |

|

8th rest |

16th note |

|

16th rest |

3. Beat

The number of beats in one measure is expressed as a fraction. The denominator indicates the type of note used as a reference, and the numerator indicates how many are included in one bar.

|

Three quarter beat | Three quarter notes in one measure. |

|

Quarter beat | Four quarter notes in one measure. |

|

Two beat | Two half notes in one measure. |

Representative music of each beat

-

Two beats

are generally used for good-tempo marches and dances. -

Three beats

are often found in dance music such as waltz and minuet. -

4 beats

The beats that you have the most opportunity to hear now. It is widely used from nursery rhymes, pops, rock, jazz, classics to jingles and ringers. -

5拍子

It is divided into 2 beats + 3 beats, 3 beats + 2 beats. It is said that it is adopted from folk music, etc., with a beat that is not found in the original western music. Typical songs include "Mission Impossible" theme songs and Dave Bluebeck's "Take Five". These are all 5 beats of 3 beats + 2 beats. -

Other

When the time signature in one work changes, it is called variable time signature. Russian composer Stravinsky's Ballet Music "Spring Festival" has measures with time signatures such as 11/4, 5/8, 9/8, 7/8, 3/8, 4/8, 7/4, 3/4 and so on. There are also things that change with time. It is difficult to play these kinds of works. In addition, the theme song of "Godzilla" is in a relatively familiar place. It is a famous phrase familiar to the ear, but the basic melody is 9 beats with 4 beats + 5 beats. In addition, it can be said that the well-known Japanese nursery rhyme “Anta gata doko sa” is a variable beat, with 4/4, 3/4, 2/4 beats intertwined.

4. How to proceed with score

Scores basically progress from the first measure, but when repeating the same measure, various repetition symbols are used according to different rules.

Repetition symbol

| symbol | How to read | meaning |

|---|---|---|

|

repeat | Go back to the previous or the beginning of the song and repeat. or the beginning of the song and repeat. |

|

Volta bracket (1st-time bar) | Play only the first iteration. |

|

Volta brackets (2nd-time bar) | Play this only for the second iteration (skip first bracket). |

|

Da Capo | The meaning of "from the beginning". I will return to the beginning of the song. |  |

Da Segno | Return to the |

|

Fine | After returning with DC or DS, it ends here. |

|

To coda | Conclusion. Jump to |

-

Proceed in the order A → B → A → B → C → D → C → D.

-

Proceed in the order A → B → C → A → B → D.

-

Proceed in the order A → B → C → D → A → B.

-

Proceed in the order A → B → C → D → B → C.

-

Proceed in the order A → B → C → D → A → B → E → F.

5. About various symbols

A symbol representing speed

This represents the speed at which quarter notes are played 60 times a minute. It is the same speed as the second hand of a clock. The higher the number, the faster the tempo, and the smaller the number, the slower the speed.

Common speed symbol

| Largo | Very slowly |

| Lento | Slowly |

| Adagio | Gently |

| Andante | At walking speed |

| Moderato | At medium speed |

| Allegretto | Somewhat faster |

| Allegro | Quickly |

| Vivace | Fast |

| Presto | Rapid |

6. Pitch and scale

Pitch means the gap between two sounds and is expressed by a frequency. A scale is made by the collection of the pitches.

Pitch

The pitch can be divided into complete, long and short, and increment / decrement frequencies.

-

Complete system pitch

1 degree, 4 degrees, 5 degrees, 8 degrees

- 1 is do and do. There is no gap because it sounds the same. This is called a complete one.

- 2 is do and fa. The fa is the fourth sound counted from the do, so it is 4 degrees. In this way, the 4th pitch including one semitone is called 4th perfect.

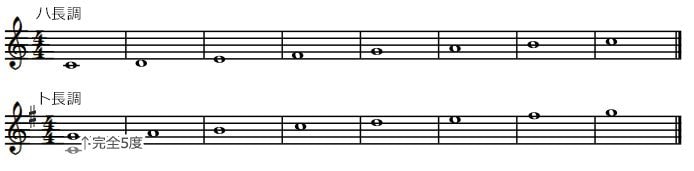

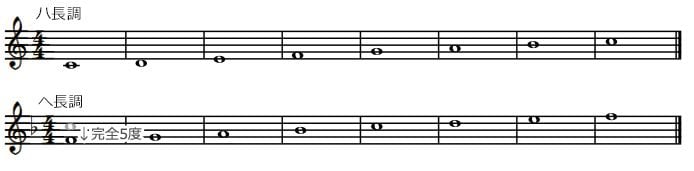

- 3 is do and so. The so is the fifth sound counted from the do, so it will be 5 degrees. In this way, the 5th pitch including one semitone is called the complete 5th.

- It is 4th and 4th, but it is 8 degrees because it is the 8th sound counting from 1st do. This is called 8 degrees full.

The above is the pitch of a complete system. The perfect pitch sounds well harmonized and pleasant.

-

Long and short pitches

2度、3度、6度、7度

- 1 is do and re. It will be 2 degrees long with full sound.

- 2 is Mi and Fa. It will be semi-short and twice short. The second and the third do not pinch the black key and will also be short.

- 3 is do and mi. Three degrees consisting of two whole tones of do and re, re and mi. Such a 3rd pitch is called 3rd major.

- 4 is re and fa. Three times consisting of a whole tone called Re and Mi and a half tone called Mi and Fa. Such a third pitch is called a short third.

- 5 is do and la. This includes one semitone (mi and fa). Such a 6-degree pitch is called 6 major degrees.

- 6 is mi and do. This includes two semitones (Mi and Fa, and Si and Do). Such a six-degree pitch is called a minor sixth.

- 7 is do and si. This includes one semitone (mi and fa). Such a 7-degree pitch is called 7 major degrees.

- 8 is Mi and Re. This includes two semitones (Mi and Fa, and Si and De). Such a 7-degree pitch is called a minor 7-degree.

The above is the pitch of long and short systems.

-

Pitch of change system

4 degrees, 5 degrees

- 1 is fa and si. Although it is a four-degree interval, it does not include semitones. Such a pitch is called 4 degrees of increase.

- 2 is Si and Fa. It is a five-degree interval, but includes two semitones (S, D, M, and F) in it. This is a 5th pitch is 5th degree

The above is the pitch of the increase / decrease system. An increase of 4 degrees and a decrease of 5 degrees creates dissonance.

| Half-tone frequency | Once | 8 degrees | 4.5 degrees | 2 or 3 degrees | 6-7 degrees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Perfect | Increase | Long | ||

| 1 | Perfect | Short | Long | ||

| 2 | Perfect | Decrease | Short |

Scale

It becomes a scale when the pitches gather with regularity.

-

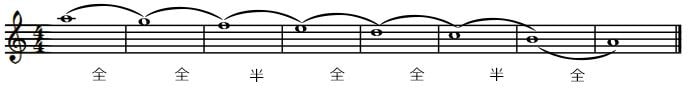

Major scale

伊 ド レ ミ ファ ソ ラ シ ド 日 ハ ニ ホ ヘ ト イ ロ ハ 英 C(シー) D(ディー) E(イー) F(エフ) G(ジー) A(エー) B(ビー) C(シー) 独 C(ツェー) D(デー) E(エー) F(エフ) G(ゲー) A(アー) H(ハー) C(ツェー) 度数 I(主音) II III IV(下属音) V(属音) VI VII(導音) VIII It becomes like the above when making a major scale with do (ha) as a tonic. In terms of piano keys, it is a scale in which white keys are played in order from "do" to "do" one octave higher. The major scale that starts from Do in this way is called "C major". In addition, major in German is called dur (Dur) and in English it is called major (Major), and it will be C dur ??and C major, respectively. The major scale is always formed at intervals of one degree (tonal) to "whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half". Therefore, # and ♭ will be attached by the tonic.

For example, what if the tonic is "f major" in Fa?

If you look at the interval from "fa" to "fa" one octave higher, it becomes "all, all, all, half, all, all, half". In order to make this "whole, whole, half, whole, whole, half", it is sufficient to add "♭" that reduces the sound of "si", which is the fourth sound, by half a tone.

There is no need to worry about ♯ or ♭ if you just remember the rules “all, all, half, all, all, half”.

-

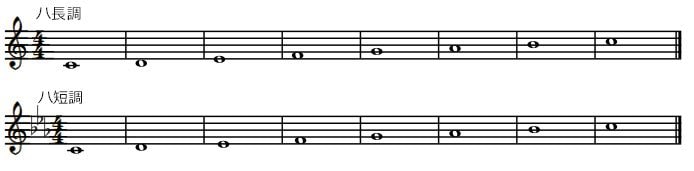

Minor scale

The minor scale is the scale three minor degrees below the major scale. The interval of the sound from the tonic is "whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole".

Unlike major scales, there are three types of minor scales. As mentioned above, the sequence of "whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole" is called a natural minor scale.

Next, the 7th note is raised by a semitone, and the scale with the sound that makes it easy to lead to the tonic is called the harmonic minor scale.

This time, the intervals are "whole, half, whole, whole, half, increase, whole" and the pitches of the sixth and seventh sounds are increased by 2 degrees. By raising the sixth note also by a half tone, it is possible to avoid an increase of 2 degrees. This scale is called melodic minor scale. The melodic minor scale is the same as the natural minor scale when going down, and it is also a major feature that the form differs between the going up and down.

The upper line is "whole, half, whole, whole, whole, whole, half", and the lower line is "whole, whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole" as well as the natural minor scale down.

Key

Most of the music we usually hear is melody (master melody) and accompaniment (chord) that is the foundation of it. The melody and accompaniment have central sounds, and music composed based on the central sound (the tonic) is called "tonal music".

-

The keynote

is mainly divided into major and minor, and the major scale is called major and the minor scale is called minor. For example, in the case of a major tune having a major tone of do (ha tone), a minor chord having a major tone of C major (in English: C major, German: C dur), and a major note (in ra). : A minor, Germany: A mol) This is similar to the explanation on the scale. -

The key signature

As explained in the section of Keynote scales, the interval of the sound of the major scale is "whole, whole, half, whole, whole, half," and the minor scale is "whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole". If it is C major or B minor, there is no need to put a ♯ or ♭.

However, if the tonic changes, it will be necessary to put a ♯ or ♭ in order to make the above alignment.

Take, for example, the case where the tonic is soft.

If you don't put a ♯ on the 7th sound "fa", it will become "whole, whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole " and not a major scale.

But what about in D major?

Now there are two #.

Depending on where the tonic is located, the number and type of symbols applied vary.

In the case of the D major, it is difficult to write a # every time a "fa" or "do" appears throughout the song. By notating this next to the clef (a treble clef or a clef), it means that "fa" and "do" will be raised semitones through the song.

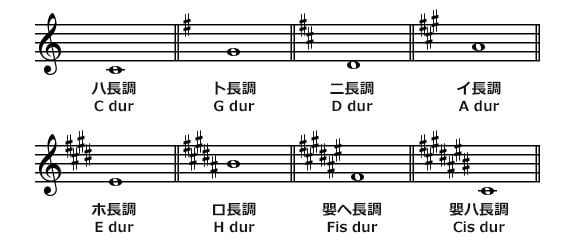

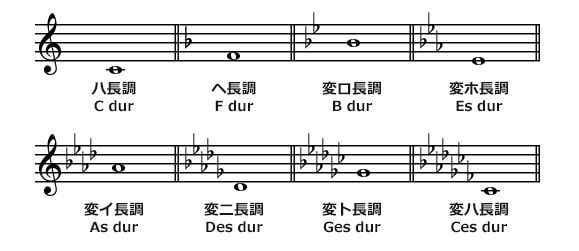

This is called a key signature.The tone is divided into a sharp system and a flat system, and there are major and minor tones in which all 12 tones from do to si are tonics.

Sharp's signature

Flat type signature

In this way there are two ♯ "do" and "fa" in "fa", if there are three #, they are "fa" and "do", "so" ・ ・ ・

In the same way, if there is one ♭, it is “si”; 2 ♭ are “si” and “mi”; if there are three ♭, they are “Si”, and “Mi” and “La”.

# order

「" Fa "→" Do"→" So "→" Re "→" La "→" Mi "→" Si "

♭order

"Si" → "Mi" → "La" → "Re" → "So" → "Do" → "Fa"

I think there are some people who have noticed, but if you go from the other side, they will be replaced.

"Fado soleramisi", "Similare Sodofa" Let's remember this order by all means!

♯ starts from "fa" and is "five" on complete 5 degrees, and "so" on complete five degrees ... "

♭" starts from "si" and "mi" on complete five degrees and also its complete. There is a regularity of "La" under 5 degrees.

And the same applies to the relationship between key signature and key tone, where the key with one ♯ is G major, the key with two # is D major, and so on with one ♭ (F major 2) If it is two, change in B major and ... and C major without key signature. There is regularity.

♯ ♭ 長調 短調 0 (12)= 0 ハ(C) イ(Am) 1 (11) ト(G) ホ(Em) 2 (10) ニ(D) ロ(Bm) 3 (9) イ(A) 嬰ヘ(F♯m) 4 (8) ホ(E) 嬰ハ(C♯m) 5 7 ロ(B)= 変ハ(C♭) 嬰ト(G♯m) = 変イ(A♭m) 6 6 嬰ヘ(F♯) = 変ト(G♭) 嬰ニ(D♯m) = 変ホ(E♭m) 7 5 嬰ハ(C♯) = 変ニ(D♭) 嬰イ(A♯m) = 変ロ(B♭m) (8) 4 変イ(A♭) ヘ(Fm) (9) 3 変ホ(E♭) ハ(Cm) (10) 2 変ロ(B♭) ト(Gm) (11) 1 ヘ(F) ニ(Dm) (12)= 0 0 ハ(C) イ(Am) Relationship key

As shown in the table above, one key signature has major and minor tones, and the relationship between each major signature and the major signature is indicated by the same key signature. This is called "parallel tone".

For example, if there is no key signature, in C major, (A minor).

If there is one, the major tone (E minor) which is a minor tone that is 3 degrees shorter than the major tone (G major).

Then how about one? You already know.

For D major (F major), D minor (D minor).

As with parallel tones, the tones used in the scale are compared with each other, and the tones containing many of the same tones are called close relatives.

There are genera, subordinate, parallel, and dominant in close relatives.The generic tone is the same tone with a tonic over 5 degrees. (G major for C major)

- The generic tone is the same tone with a tonic over 5 degrees. (G major for C major)

- Subordinate tone is the same tone whose tonic is completely 5 degrees below. (To C major to C major)

- Parallel tone, as mentioned above, has the same major and minor relationship between key signatures. (A to A major)

- The major tone is the relationship between the major and minor key tones. (A minor to C major)

Then what happens to the minor relatives? Let's take a minor example as an example.

- The generic tone is the same minor tone as the tonic is completely over 5 degrees, so it is E minor.

- Subordinate tone is a D minor tone because the tonic is the same tone completely below 5 degrees.

- Parallel tone has the same major and minor key relationship, so it is C major.

- The major tone is the relationship between major and minor in the same major tone, so it is a major.

In this way, all the tones have a close relative and are mutually related.

modulation

The songs we usually listen to are not all based on just one tone, and the tone may change in one song. This is called modulation. In this case, the modulation to these close relatives is most commonly used, and the music flows naturally. Recently, a lot of modulations have been heard that effectively aim for the sense of incongruity due to the modulation to the distant tone.